I learned this today when talking with someone I respect: It takes faith to be a leader when leading means being you despite the sharp, cracked edges that come with your personality, the spicy language out of your mouth and the inability to do subtle well, the expectation that you’ll be honest even when you can’t be kind, and the ever-increasing call to be a better you without losing you.

I learned this today when talking with someone I respect: It takes faith to be a leader when leading means being you despite the sharp, cracked edges that come with your personality, the spicy language out of your mouth and the inability to do subtle well, the expectation that you’ll be honest even when you can’t be kind, and the ever-increasing call to be a better you without losing you.

Category / Faith-Related

This category is like Interior except that it covers faith and spirituality.

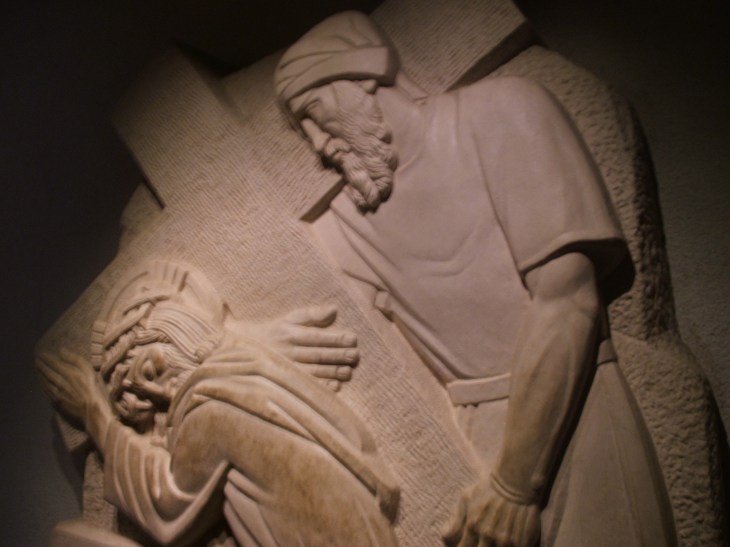

For Ash Wednesday, For Awaiting Souls

In the out of the way places of the heart,

In the out of the way places of the heart,

Where your thoughts never think to wander,

this beginning has been quietly forming,

Waiting until you were ready to emerge.

Though your destination is not yet clear

You can trust the promise of this opening;

Unfurl yourself into the grace of beginning

That is at one with your life’s desire.

Awaken your spirit to adventure;

Hold nothing back, learn to find ease in risk;

Soon you will be home in a new rhythm,

For your soul senses the world that awaits you.

From John O’Donohue’s To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings

“…complete these necessary endings.”

When I heard of Pope Benedict’s resignation, after I got over that popes actually could resign, I thought of Henry Cloud’s book, Necessary Endings.

The pope’s historic decision is a surprise to many. I am prayerful for the church that Benedict leads, that it may be pastored by its Good Shepherd. Whatever the implications of the pope’s choice, the differences between him and previous bishops of Rome as they’ve faced physical decline and increasing responsibility, I hope it also turns into a model of courage, an example of how catholics discern. May it be that for us non-catholics, too.

Here’s a quote from Dr. Cloud; may it be helpful as we pray for our catholic brothers and sisters and for the entire church community:

Something about the leaders’ personal makeup gets in their way. Leaders are people, and people have issues that get in the way of the best-made ideas, plans, and realities. And when it comes to endings, there is no shortage of issues that keep people stuck.

Somewhere along the line, we have not been equipped with the discernment, courage, and skills needed to initiate, follow through, and complete these necessary endings. We are not prepared to go where we need to go. So we do not clearly see the need to end something, or we maintain false hope, or we just are not able to do it. As a result, we stay stuck in what should now be in our past.

One Reason To Be Grateful

The conversation–dreaded for all the unknowns hidden underneath your specific need–with that person you know only by what wrong you’re seeking to speak to them about, when, in the small space of eight minutes, you will explain how they’ve mistreated you and when you will tell them without telling them that they need to change, and they will accept what you’ve said like a gift, and you’ll really see grace and splendor because it could have gone in a dozen wrong directions.

The Problem With Commandments

I’m reading a book about the 10 commandments. The book is old by many people’s standards, published in way back in 1999, by Hauerwas & Willimon.

I think I’m starting a journey to reading everything Hauerwas has written. I started with his memoir last year at David Swanson’s suggestion. Hauerwas makes Christianity seem both accessible and incredible for it’s simplicity. He and Will Willimon often get together, join literary powers, and paint this faith beautifully.

This slim volume on the commands is just as intriguing. Their premise, or one of them, is that the commandments only make sense if we have as a background the vocation of worshipping God. God is not to be helpful or responsive to us but worshipped. God is, and creation worships. In their own words:

The commandments are not guidelines for humanity in general. They are a countercultural way of life for those who know who they are and whose they are. Their function is not to keep American culture running smoothly, but rather to produce a people who are, in our daily lives, a sign, a signal, a witness that God has not left the world to its own devices.

You may disagree, but those sentences clarify the ten words (another way of talking about the commands is by using the earlier phrase “ten words”), but they also make them that much more dubious in that clarity. They are both sensible and nonsensical, which is how they come to the language of these acts being countercultural.

This quote below is actually about an early theologian, Thomas Aquinas, and their summary of something Aquinas said. But the quote is searching me right up through here. It is in the chapter on the fifth commandment not to murder. By this point in the chapter, they’ve hinted at how murder is a term that captures all kinds of killing and that they scripture’s intent is both external and internal. So think about behaviors and thoughts:

Aquinas does not mean that we are not to feel righteous indignation against injustice, but rather that we are to develop among ourselves those virtues that free us from temptation to envy and self-importance, which so often lead to presumptions that we have been grievously wronged.

I’m thinking about this in relation to being a father, thinking about this as a leader, as a husband, as an opinionated person. And the less the commandments are about the external only (i.e., murdering a person), the more challenging they become. I’m pretty sure I’ll see coming the whole me-murdering-somebody-thing. It’s external. But the internal killing is taken up into this commandment, too, and when I believe that, when I believe that God who is concerned for thoughts from afar or “lust” as Jesus has so said, I have an existing problem with the commandments. I feel both inspired to live into this vocation as a person before God and knocked to my knees. At some point, I get really thankful that grace is both fulfilling and inspiring. At some point. For now, I taste that problem on my tongue.

The Problem With Commandments

I’m reading a book about the 10 commandments. The book is old by many people’s standards, published in way back in 1999, by Hauerwas & Willimon.

I think I’m starting a journey to reading everything Hauerwas has written. I started with his memoir last year at David Swanson’s suggestion. Hauerwas makes Christianity seem both accessible and incredible for it’s simplicity. He and Will Willimon often get together, join literary powers, and paint this faith beautifully.

This slim volume on the commands is just as intriguing. Their premise, or one of them, is that the commandments only make sense if we have as a background the vocation of worshipping God. God is not to be helpful or responsive to us but worshipped. God is, and creation worships. In their own words:

The commandments are not guidelines for humanity in general. They are a countercultural way of life for those who know who they are and whose they are. Their function is not to keep American culture running smoothly, but rather to produce a people who are, in our daily lives, a sign, a signal, a witness that God has not left the world to its own devices.

You may disagree, but those sentences clarify the ten words (another way of talking about the commands is by using the earlier phrase “ten words”), but they also make them that much more dubious in that clarity. They are both sensible and nonsensical, which is how they come to the language of these acts being countercultural.

This quote below is actually about an early theologian, Thomas Aquinas, and their summary of something Aquinas said. But the quote is searching me right up through here. It is in the chapter on the fifth commandment not to murder. By this point in the chapter, they’ve hinted at how murder is a term that captures all kinds of killing and that they scripture’s intent is both external and internal. So think about behaviors and thoughts:

Aquinas does not mean that we are not to feel righteous indignation against injustice, but rather that we are to develop among ourselves those virtues that free us from temptation to envy and self-importance, which so often lead to presumptions that we have been grievously wronged.

I’m thinking about this in relation to being a father, thinking about this as a leader, as a husband, as an opinionated person. And the less the commandments are about the external only (i.e., murdering a person), the more challenging they become. I’m pretty sure I’ll see coming the whole me-murdering-somebody-thing. It’s external. But the internal killing is taken up into this commandment, too, and when I believe that, when I believe that God who is concerned for thoughts from afar or “lust” as Jesus has so said, I have an existing problem with the commandments. I feel both inspired to live into this vocation as a person before God and knocked to my knees. At some point, I get really thankful that grace is both fulfilling and inspiring. At some point. For now, I taste that problem on my tongue.

Wouldn’t Quite Call This A Reflection

It is debilitating to read or hear about another murdered child, another known and unknown murderer, another set of families who have forever been changed by tragedy, another lukewarm, if present, response by various onlookers, be they leaders or church people or neighbors or strangers.

There are surely words to say, aches to verbalize, phrases to pray. And then there is the throat-grabbing shock of violence, that first, almost innocent, feeling that’s snatched away a little at a time when a child’s life is taken. Every life matters. Every person is honorable. And yet there is something gross and unshapely when a child’s life is taken. Whether or not we stop and pay attention. Whether the story goes unreported or shared. Whether people come near those families and remind them how real it is that things, in a way, will never get better for them.

The fantastic, appalling nature of the murder of a child sinks in deeper and deeper, and it makes you question substantial things.

I don’t intend this to be trite at all. If anything, I’m contextualizing my question with the above-mentioned call for silence. Still, my question for you: Does your faith or faith tradition say anything about such things?

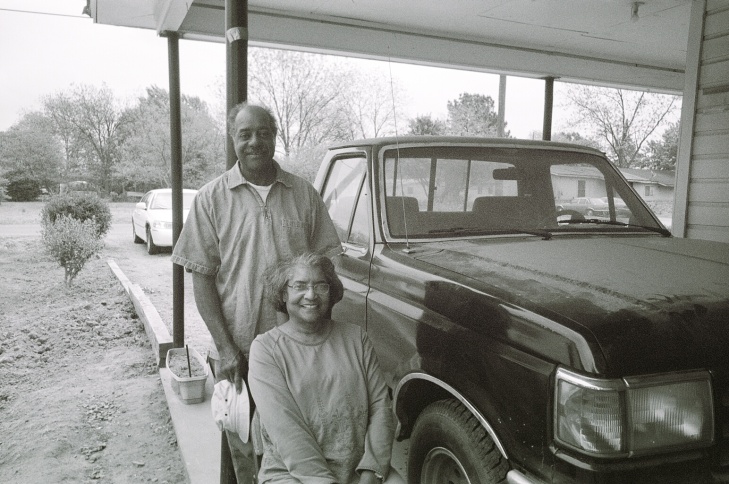

Reflection on Resurrection & Mardell Culley, Sr.

I think that sermons are oral documents, best heard and not read, but as a memory for myself and an invitation to you, I’m posting the notes of my eulogy for my father. I preached it yesterday, and while it doesn’t include necessary spontaneous elements which come from being in the preaching moment, I did stay close to my notes.

I often say in situations like this that there are, at least, two aspects to a eulogy: one that looks backward and one that looks ahead. The backward part turns our vision to yesterday, and we remember what we’ve lived and felt and experienced from the deceased. We reflect on things. We laugh at jokes. We tear up because of tender moments that nobody else shared but us and the dead person.

Alexander Maclaren, a late 19th century preacher, said, “Most men have to die before their true beauty is discerned.” That true beauty is often seen and reflected in the stories we tell about those men. Perhaps also in the stories we don’t tell. There are things worth saying about my father, Mardell Culley, Sr. Some of them have been said, some only considered. I’ve thought of my time with pop. You’ve probably thought of your time with him, as a friend, a brother, a neighbor. Like me, you know him as an usher in the church, as a relative, as a man who drank a beer occasionally—as a man who drank too many beers occasionally. But as helpful as it may be, I don’t want to dwell in that backward glance today. I want to sit with that second part of the eulogy, the part that turns our gaze ahead. And to focus our collective vision, I want to do what anchors me as a Christian: to see scripture.

The passage in John is about Jesus after he’s been told of his friend Lazarus’s death. Jesus was with his disciples when he received the news. He delayed their leaving to go and see about Lazarus’s remains and the sister friends, Mary and Martha who were grieving. The passage has Jesus turning his soul inward before he travels on the road to Bethany. The Bible says that Jesus did what all of us do when we love, wept for a friend. Have you ever wept? Maybe you didn’t shed tears but your heart ached in your own way—you wept. Over your children, at a loved one’s descent into addiction, while confused, or something else… If you love, you will weep.

JOHN 11:44 says, The man who had died came out, his hands and feet bound with linen strips, and his face wrapped with a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.”

There is more detail before this ministry of Jesus. There are questions raised, answers given, prayers offered. And then Jesus calls for the dead man. I read that this passage about what Jesus does for Lazarus is a confirmation and a promise. Jesus miraculously resuscitates Lazarus. He comes out of the grave and is unwrapped so that he lives, so that he has more time on this side of eternity. In doing this, the Lord shows us a picture of his own future. We get a slice of what Jesus himself will experience—death and power over death. Now, Lazarus eventually dies again. Jesus, though, readies us as readers and listeners for what is to come: resurrected life. Jesus will rise from the grave by God’s own power, and this passage readies us for such an event. It prepares us for our own deaths in light of the resurrection. It is a confirmation and a promise. When Lazarus rises in this passage, we hear scripture telling us that what happened to him, in preliminary form, is a foretaste of what will come for all people in complete form.

As I prepared for today, I wanted to tell you something about my father, something from my experience of him, which is different from my brothers, from my aunts, from Mr. Robert Bell. I’ve made lists in my head of things that I’ve recalled about daddy.

I’ve thought about things that he told me, things I’ve seen him do, lessons I believe I’m learning from him. But rather than go into that, I thought of something more meaningful, at least, in my opinion, and the most meaningful thing I can tell you about my father is that he is loved by God. That’s a deceptively simple thing to say, but I think it’s the most important thing I can tell you about Mardell Culley, Sr.: He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God.

There are surely other things to say, and then again, there really isn’t more beyond this in my mind, perhaps other than the fact that my father knew he was so loved. Yes, pop was a man with pain and memory and hurt and disease. Yes, pop was wrestled in the mind by slow, ravaging dementia, unsettled by strokes and a failing brain. Pop was angry from a loss of independence, from not being able to drive where he wanted, when he wanted. Yes, pop was a stubborn man, a man spoiled by people, chiefly his sisters as far as I can tell; a man with a grin so infectious it could make you grin whether you wanted to or not. There are other things to say, but atop that list for me today is that pop is loved by God. Not some version of my father but him. The man who got angrier as his frustrations grew. That man is loved by God. The man who couldn’t remember that you had been there moments after you left his room. That man is loved by God. The man who yelled and didn’t take his medicine even though he was usually mild-mannered. That man is loved by God. The man who wasn’t a perfect father to any of his sons, who wasn’t a perfect brother or a perfect friend. That man is loved by God.

I tell you that like Lazarus in the gospel and like Mardell Culley who lived his last days in a nursing home completely against his best will—like these men who are loved by God—you and I are also loved. Lazarus and my father, men who reflect a truth that is so large it’s incredible, are mirrors for us today: we, as we are, sit loved by God. We, imperfect as we are, are perfectly acceptable to God. We, with our bruises and our egos and our faults, are wanted and desired so by God that Jesus comes to us and offers a splendid future where resurrection is normal.

Resurrected life, in part, means life where God is immediately present. I cannot imagine all that it means, but living on that other side of breath has to mean living in response to the limitless freedom that comes with no pain and only love. What would that be for you? Would it be a meeting with some family member who has died? Would your resurrected life look like lowered blood pressure or stronger legs so that you could walk or run or leap as long as you want? Would resurrected life mean courage and the absence of fear? Would it mean that you could rest without having so many things to do? These words in John’s gospel pull us to embody what it means for God to be immediate and present. That’s our invitation today.

Among my last words to my father was a prayer. I asked him at the acute care hospital in Searcy whether I could pray with him. He bowed his head, tipping the white rain cap he was wearing. He was fond of those hats—hats in general. He had a large leather hat that was probably as old as me, but in this case, he wore a white hat with a thin blue stripe. When he turned to bow, I took his thin, frail arm and bowed my head. He prayed with me, for what I think was the first time, if I don’t get count thanksgiving for a meal.

When I last spoke with pop, it was days later, Monday, Christmas Eve. Aunt Lynnie called while she at the nursing home and gave daddy the phone. We talked briefly—him asking about Bryce and Dawn, me asking about him and if he’d gotten adjusted to being back at Robinson Nursing Home. Aunt Mose was coming into the room while we were on the phone. There was a lift in my father’s voice. He wasn’t moaning or whispering. He wasn’t muttering the way he often had when he was upset or ready for you to leave his company. I thought he was getting better. I didn’t know he was leaving. I didn’t know at the time that his was the tone of a man getting ready to respond to the immediate presence of God. I’d like to think that my father’s favorite holidays were the ones where he bought some of us gifts. But Daddy would celebrate Christmas thinking of Jesus who he would soon see. My father had his best Christmas ever this year. Even with the lack of an appetite. Even with the chest pains which caused our final alarms. Daddy knew Tuesday and Wednesday that he was going the way his brothers had gone, the way Lazarus had gone. He would see the Lord, the giver of Life. Mardell Culley got the confirmation and the promise.

Pray with me: Oh, God who gives resurrected life, thank you for the chance to know my father, the opportunities to love him and be loved by him. Thank you for every person who showed him kindness, who aided him in recovering and healing. Thank you for his sisters, these beautiful women who have suffered all these times in closing the coffins of their brothers and for how you have sustained them under such grief. Thank you for my brothers and our relatives who have all had our own unique relationships with my father and for how you have blessed us with memories to cherish. Now, Lord, give us unwavering faith, as we leave this place, even if that faith is thin or frail or hardly visible. Grant that we may see the true beauty of this beloved man, and grant that we may discern the true beauty of his savior. Open our eyes to the wonder of every possibility that comes with life in you. Keep company with us from this day on so that we might live as if death will, indeed, come for us. Convince us of your promises to us and confirm your love for us as people who can only accept your unconditional love. We ask these things in the name of the One who beat death and whose victory changed everything, Jesus. Amen.

The Breath Prayer I’m Praying at Pop’s Funeral

These are the words I’m breathing today as we celebrate, remember, grieve further, and hear the good news. They come from John 11, the scene where a weeping Jesus raises a dead friend.

Did I not tell you that if you believed you would see the glory of God?

I’m breathing and praying that last phrase, that God would help me see the glory, help me spot the splendor, notice the Presence. Pick one of those phrases and pray it for yourself. We’ll pray together today.

Bryce with Dawn at Christmas Service

Christmas Reminder from Dr. Gardner Taylor

This is the glory and pain of my work as preacher, never more so than today. There is much that I see and know about Jesus Christ, but I cannot say it. One feels sometimes, with Robertson Nicoll, that “the desire to explain [the atonement] Christ may go too far. The reality of Jesus Christ is much more readily understood than many explanations. Its onlyness is the main thing.” Every preacher must feel sometimes like the woman who said, “I understand who Jesus Christ is and what he does for me. I understand it well until some one ask me to explain it.” Well, the preacher’s job is to explain and proclaim Jesus Christ, and it is too big a subject for any human lips to speak. So! This sermon will be a failure, but may it be a godly failure and give honor to the Lord who calls it forth…

…Now I would want to fasten this morning upon those two titles joined together: Jesus Christ. Here is what all of our preaching is about: Jesus Christ. Here is what all of our believing is all about: Jesus Christ. Here is what all of our community work is about: Jesus Christ. What we do in the projects and enterprises we have undertaken here, unmatched in scope and versatility by any voluntary group of black people in the history of this city, is all done not as something aside from, separate from, but as a result of Jesus Christ and our relationship to him. I want to talk about him this morning and see how in him we are blessed. “Thou shalt call his name Jesus” (Matthew 1:21). That was the signal at the birth of our Lord that we have in him a reality. A man, a person.

Now, it is impossible to overestimate the importance of Jesus as man, person, one of us, “a man for others,” as Dietrich Bonhoeffer called him. The Heidelberg New Testament Professor, Gunther Bornkamm, stresses that in the Gospels we have an emphasis upon the person of Jesus. The writers stress the authority of his words, what he said, and the authority of his deeds, what he did. Ours is not a misty, thin, airy faith, no pious fantasy without living reality. I wish that people would some day understand that. Ours is an earthy faith, not something way out somewhere from the reality we know. If people understood that they might see Christian people in a different light rather than the muddle-headed, thick-witted notion passing for shrewdness which assumes that when you see a Christian you see a dunce, that to be tender-hearted one must be soft-headed. Stupid!

Our Lord lived here.

A small portion of Dr. Taylor’s message, “Jesus Christ,” preached March 20, 1977.

Dancing with Death

When I started blogging, my friend David told me to blog about the things that I think about, the things that matter to me. Lately I’ve been thinking about the decline of my father’s health. That’s why I’m posting this on both blogs. I’ve not had much free mental space over the last few months because my dad has been there taking it up with a thousand questions of varying sizes and shapes.

My dad is demented, meaning, he has dementia. What is the appropriate form for that sentence? Is my father demented? It feels like a misuse of language to have to write that way: my father has dementia. It’s one word or two too long. Plus, it isn’t true. Particularly since it feels most days like dementia has my father, like the synapses in his brain are freezing over or cracking or deteriorating or doing anything but firing in the way all my college classes suggested synapses do. I paid a lot of attention to those classes at U of I. I got mostly good grades, though I hated statistics and could have done better in Don Dulany’s course, especially if I hadn’t been devoting all that time talking to schizophrenics at strange hours through the night. But these days I’m thinking that I could have paid more attention.

Anyway, my father’s dementia and the accompanying decline in his condition is essentially unsettling. My experience of him and his health feels like all the sturdy things in my history with him are getting up, spinning around, and landing in a different place from before. It feels like every conversation with him, each road trip to Little Rock, leaves me tired from the passing lane and sweating after a long dance with this disease.

And I’m not the one doing the real dancing. I catch myself to say this. Over the last six months, since we found out about the strokes and since we’ve started to confuse (i.e., not be able to tell) the stroke’s grip for the dementia’s, I’ve remembered consciously that it’s my father who is suffering. And that’s the worse part. Not our collective suffering as we watch or join in as a family responding to our loss and grief. His suffering is the basic problem here. I can recover. Can he?

And I wonder to myself if there is a little grace in my dad not knowing how much he’s suffering. And I check myself again at the hint of such arrogance. Can my father, complex man that he is, be written off by my saying, “Well, he doesn’t realize what’s happening to him?” How can I trust that? How can I take comfort in the corrosive way the disease is handling him so that his head is all messed up, his memories following? How can I be encouraged that his brain, eating or sucking or dropping away all the memories which make him him, is so distorting his reality that he is in some way spared?

I ask these questions because I want to be spared. My father isn’t spared. We aren’t either. And these instances of death, these suspensions of time, when I’m not sure if my dad is “there” or “somewhere else,” are not healing. They are small deaths, and they are upsetting, unsettling, and disturbing. He is as pained as anyone in this. He didn’t wish for this end. And he can’t find the ways to express that any more. Not on most days. He’s the one really dancing.

Even though his feet are inching into a straddle some days and stepping normally on other days, it is my dad’s feet that I’m watching. It is his pair of legs that my eyes fell to the other day as he walked to me on the arm of that nurse. I had been buzzed into the acute care facility in Searcy, the place where they specialize in treating elderly men and women with psychiatric problems stemming from the disease I keep thinking looks like Skeletor.

He was shuffling slowly, arm wrapped in a sturdy nurse who introduced himself as Billy. Daddy recognized me and that recognition was a gift even if I was struck by my dad’s gait. It was an interior compromise, thankful for the recognition and willingness to overlook the pulchritude.

I could overlook that daddy looked bad, really bad. Bad the way he was when he had the stroke in July. Bad like when I first saw him in July, my brother Mark at my side, I was wondering where my father’s weight went. Bad like I saw him for the first time as a truly different figure, no longer the man with muscles and a bench press in his basement with weights I’d never be able to lift.

My father’s arm was attached to his nurse, straddling, dancing, and I met him the rest of the way, took the other arm, and listened to the music of his experience and started dancing with him. We walked slowly, really slowly. And instead of going to the designated room, we sat in the closest chairs. I suggested them because the distance to the room was too far for daddy after the stint from his room and too far for me after driving those eleven hours.