Tag / Writing

Those Well-Fed Hopes

This is a prayer from my journal, from an undated entry, and it’s up here in case I need to return to it. I believe I was relinquishing some things around writing at the time, but I can utter these words as I try to become a Christian:

Help me let go of those dreams, those well-fed hopes, stubborn desires even though they came mostly from places of sincerity and love and, perhaps, mystery. Grant me the freedom to choose some other life, to set some different course. Make me fearless in that choosing. Inspire me as I close and choose and change.

Attending to the Details

When history is collapsed into myth, responsibilities become diffused, and repentance and reconciliation become impossible. In the inflated realm of mythical oppression, villains are so villainous that no one sees themselves reflected on the image. Few can trace accrued privileges to specific and intentional evil acts. Similarly, victims become so quintessentially and epically victimized that all escape routes from the condition are sealed off by a maze of self-doubt, blaming, and low self-esteem. The antidote to this phenomenon is to attend to the details, to understand the specific events, ancestors, life stories, causes of oppression, and avenues of social change. Historical and spiritual specificity is salvific. Then and only then can the movement toward moral flourishing begin.

Slow But Productive Work

Have you ever thought about how long it takes to accomplish what you spend your days doing? I met with a media PR person and an architect the other day. He’s in a supervisory role at work and he is new to parenting. His wife, new to parenting as well, works to promote the events of a film center in Chicago. Both of them spend a lot of time with their son and in their jobs.

And it occurs to me that people like my meeting friends–including me–have work we’re doing that takes a while to complete. Does that make sense? Whether planning for an event, reviewing building plans, or mentoring a staff person, these things take more than one moment. They take a series of moments, meetings, and interactions. It’s slow work.

Writing, teaching, ministry, cleaning, fathering–these are all slow jobs. And slow work takes time to complete and time to appreciate.

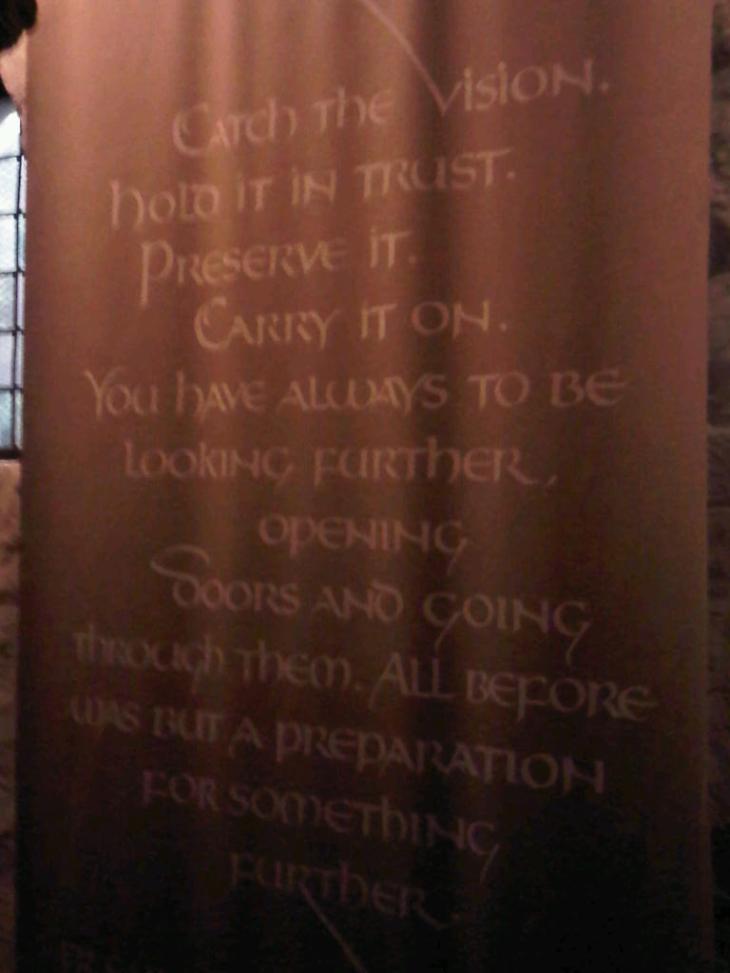

I read this in an email newsletter from Preaching Today, and it feels right for preachers and appropriate for people doing other slow work too:

Last week I talked to a pastor who nearly quit during his fifth year at Church ABC. He wanted to quit, the church wanted him to quit, but for some reason he hung in there. Now he’s in his 18th year at the same church and his preaching ministry has finally hit a sweet spot.

My point is not that you should always stick it out. My point is that deep, effective, Spirit-anointed preaching is slow work. It takes time to build trust. It takes time to hone your craft. It takes time to study a biblical text. It takes time to know your people and your cultural context. So, preacher, I urge you to accept this slow work of God. Don’t be in a hurry to change the world with one amazing sermon or one flashy sermon series. Learn the art of slow preaching, long-haul preaching, week after week preaching. It will bear more fruit than you could ever imagine.

I hope you get a glimpse that your work, whatever it is, is fruitful. Not pointless but productive. And I hope you do it as well as you can.

Two Questions From the Weekend, pt 2

As I mentioned in my last post, I had a great time leading a retreat the other day with Highrock Covenant Church in Arlington, Massachusetts. Before the Saturday retreat, I met for dinner with the two leaders helping me prepare for the day. Michelle and Amy treated me to a tasty meal at a new favorite place, Not Your Average Joes. Incidentally if I’m ever in Boston and you’re there too, you can take me there for a meal. Note that I may come with family.

During our conversation, Michelle asked me two questions. Her first was why do you lead these retreats, and I thought out loud about that in my last post. In this post, I’m rambling about her second question. The context of our retreat didn’t really relate to her second question since it was a broader, bigger question. She asked, what is your dream?

Some kind of way I was expected to answer first. So I tilted my head up and thought about the largeness of the matter. Michelle caught my thought as if it were a tossed ball and said she knew it could be answered in many ways. I knew exactly what I wanted to say. Only later, when she and Amy answered themselves, did I think I miscalculated.

Their answers would hone in on particular things they wanted to do, while mine focused on the broader answer right before that, what I wanted to be. I told them that I wanted to be a faithful pastor while being a good writer. My dream is to serve the congregation in front of me, people I know, and to serve the reader I would probably never meet. That has become a persistent abiding dream. It’s a part of the play that I think of when I close my eyes. Those two worlds combined serve as the stage on which my life is.

I’m thinking about words all the time. I’m listening to the stories of others, making sense of them, or trying to. In one role I’m sharing an old story, turning it over, researching its rudiments and investigating the world from which it was written. I’m trying to interpret that story for my life and community.

In the other role, I’m wondering through the creative process and attempting to write the story in my ear, the story in front of me, the one that, unlike the old story, resists revision right now. It’s the story I’m working over, thinking about, and going back to once I’m done writing this post.

I want to do well at both. I’m not the type to attempt something and quit. I’m destined to send myself nuts, but it’s the only route I know. I blame it on my birth order. At least today. But these two parts of me, these untraceable pieces of my character, compose my dream.

I appreciate Michelle’s question. I wonder how you would answer.

A Great Question

Are you sure this will be important to you in three years?

From Aimee Salter’s post about writing and commenting on blogs, over on Rachel Gardner’s blog. Doesn’t it fit so many occasions? I think so!

“Words Are Too Small”

Emily Allen quotes her sister friend, Sophia, who is reflecting on her son’s diagnosis and experience of Leukemia. Her son, Jacob, was experiencing hair loss around that time:

I did not cry, not there, but later when going through the pictures of hair falling off.

It’s just hair, you can say but no, it’s so much more.

It’s love.

It’s a statement.

It’s hope.

It’s pain.

It’s a side-effect.

It’s a mother’s heart.

Words are too small.

I have seen my son’s hair fall off, seen the chemotherapy side-effects, all of them.

It is hair, but it is a big deal It is part of our identity, a part we cut and style and color and pay for to feel prettier.

Without hair we look different, naked, people notice.

I know God was there, counting, every single hair that fell, every tear.

And he is there when new grows back, there in every moment.

I read this here at Rachel Held Evans’s blog.

A Prayer for Writers #1

Periodically I’ll post a written prayer for writers. Other people can pray them, but they are coming out of my writing life, out of my hopes for the writers among us, and out of my desire for this blog to sit at the intersections between faith and writing. Perhaps you can pray them, or a line from them, with and for the writers you read, know, and support. My first prayer is in response to the blank page. Pray with me, if you will.

Dear God,

Enable us to see the blank page as a gift and a friend. Whether white or yellow or some other color, brighten that background until it becomes a wide invitation from the Creator of the best stories and the Maker of the most enduring truths about humanity. See the page as we see it. Notice our fears, most of which we keep to ourselves. Count our hopes and measure the distance between what we want and what we’re able to accomplish. Track the meanings of all the unwritten words and make sense, especially when we can’t, of why writing matters to us. Make us unafraid of the page. Help us to imagine it full and crowded. Excite us over tomorrow when today’s phrases have felt forced or tired because we tried and we wrote but didn’t quite finish. Give us the skills associated with gratitude. Form us into thankful writers, people who are grateful for language and its gifts. Make us fearless as one page ends. Grant that we might see you in the blankness of what’s next. Press into us faith and imagination because writing requires both. And may we, in some way, offer you all we do. And may our offerings entertain you, the most perceptive and faithful Reader.

In the name of the One who once wrote lost words in the sand,

Amen.

From Migrations of the Heart

I’m reading Marita Golden’s autobiography, Migrations of the Heart. Her story is compelling and thoughtful and beautifully written. Can I use beautifully? It’s hard at times and yet still somehow beautiful. Her writing is striking and full and lively.

I’m reading Marita Golden’s autobiography, Migrations of the Heart. Her story is compelling and thoughtful and beautifully written. Can I use beautifully? It’s hard at times and yet still somehow beautiful. Her writing is striking and full and lively.

In this passage, she’s writing about a very powerful loss. Her first pregnancy ended with what her doctor called a spontaneous abortion. Ms. Golden is “taking me to school” in her writing. I’m learning. I’m listening. As she’s talked about her experiences in this autobiography of loving Femi, a Nigerian, and moving into his culture after having lived for years in the US, I’m learning, through her, of what it took for her to adjust. New expectations, new rules, spoken and unspoken. I’m learning of how manhood and womanhood was seen and expressed in her life. I’m learning about being a husband.

At home I recuperated, confined by the doctor, Femi and my own desire to bed. Almost immediately I began to write furiously, with the fervor of a long-awaited eruption. I filled page after page with an outpouring the loss of my child released. The writing affirmed me, anointed me with a sense of purpose. Most of all, it slowly began to dissipate the sense of failure that squatted, a mannerless intruder, inside my spirit. The writing redeemed my talent for creation and, as the days passed, made me whole once again.

In the evenings Bisi came to visit, and for several days under her hand I received a postpartum “native treatment.” Filling the tub with warm water and an assortment of leaves, grasses and herbs, her hands pressed and gently kneaded my stomach in a downward motion. “This will bring out the poisons,” she explained. The water was the color of strong tea and the steam rising from it made me drowsy. Drying me with a towel, she warned, “Tell uncle to let you rest. Let your body heal. Tell him to be patient.”

“I will,” I assured her, “I will.”

Mourning the loss of his child, his son, Femi inhabited the house with me but was dazed with grief. As I ate dinner from a tray in bed one evening, he said, “We lost a man.”

“No, Femi, we lost a child.”

“We lost my son,” he insisted. “And we must find out why this happened. What went wrong, so that it won’t happen again. Next time you will not drive; the roads alone could cause a miscarriage.”

“Femi, the doctor told me that sometimes a weak or defective fetus will spontaneously abort. That perhaps if the child had gone nine months, it may not have been a healthy baby anyway.”

In response he quieted me with a wave of his hand. “We will be more careful next time.”