I think that sermons are oral documents, best heard and not read, but as a memory for myself and an invitation to you, I’m posting the notes of my eulogy for my father. I preached it yesterday, and while it doesn’t include necessary spontaneous elements which come from being in the preaching moment, I did stay close to my notes.

I often say in situations like this that there are, at least, two aspects to a eulogy: one that looks backward and one that looks ahead. The backward part turns our vision to yesterday, and we remember what we’ve lived and felt and experienced from the deceased. We reflect on things. We laugh at jokes. We tear up because of tender moments that nobody else shared but us and the dead person.

Alexander Maclaren, a late 19th century preacher, said, “Most men have to die before their true beauty is discerned.” That true beauty is often seen and reflected in the stories we tell about those men. Perhaps also in the stories we don’t tell. There are things worth saying about my father, Mardell Culley, Sr. Some of them have been said, some only considered. I’ve thought of my time with pop. You’ve probably thought of your time with him, as a friend, a brother, a neighbor. Like me, you know him as an usher in the church, as a relative, as a man who drank a beer occasionally—as a man who drank too many beers occasionally. But as helpful as it may be, I don’t want to dwell in that backward glance today. I want to sit with that second part of the eulogy, the part that turns our gaze ahead. And to focus our collective vision, I want to do what anchors me as a Christian: to see scripture.

The passage in John is about Jesus after he’s been told of his friend Lazarus’s death. Jesus was with his disciples when he received the news. He delayed their leaving to go and see about Lazarus’s remains and the sister friends, Mary and Martha who were grieving. The passage has Jesus turning his soul inward before he travels on the road to Bethany. The Bible says that Jesus did what all of us do when we love, wept for a friend. Have you ever wept? Maybe you didn’t shed tears but your heart ached in your own way—you wept. Over your children, at a loved one’s descent into addiction, while confused, or something else… If you love, you will weep.

JOHN 11:44 says, The man who had died came out, his hands and feet bound with linen strips, and his face wrapped with a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.”

There is more detail before this ministry of Jesus. There are questions raised, answers given, prayers offered. And then Jesus calls for the dead man. I read that this passage about what Jesus does for Lazarus is a confirmation and a promise. Jesus miraculously resuscitates Lazarus. He comes out of the grave and is unwrapped so that he lives, so that he has more time on this side of eternity. In doing this, the Lord shows us a picture of his own future. We get a slice of what Jesus himself will experience—death and power over death. Now, Lazarus eventually dies again. Jesus, though, readies us as readers and listeners for what is to come: resurrected life. Jesus will rise from the grave by God’s own power, and this passage readies us for such an event. It prepares us for our own deaths in light of the resurrection. It is a confirmation and a promise. When Lazarus rises in this passage, we hear scripture telling us that what happened to him, in preliminary form, is a foretaste of what will come for all people in complete form.

As I prepared for today, I wanted to tell you something about my father, something from my experience of him, which is different from my brothers, from my aunts, from Mr. Robert Bell. I’ve made lists in my head of things that I’ve recalled about daddy.

I’ve thought about things that he told me, things I’ve seen him do, lessons I believe I’m learning from him. But rather than go into that, I thought of something more meaningful, at least, in my opinion, and the most meaningful thing I can tell you about my father is that he is loved by God. That’s a deceptively simple thing to say, but I think it’s the most important thing I can tell you about Mardell Culley, Sr.: He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God. He is loved by God.

There are surely other things to say, and then again, there really isn’t more beyond this in my mind, perhaps other than the fact that my father knew he was so loved. Yes, pop was a man with pain and memory and hurt and disease. Yes, pop was wrestled in the mind by slow, ravaging dementia, unsettled by strokes and a failing brain. Pop was angry from a loss of independence, from not being able to drive where he wanted, when he wanted. Yes, pop was a stubborn man, a man spoiled by people, chiefly his sisters as far as I can tell; a man with a grin so infectious it could make you grin whether you wanted to or not. There are other things to say, but atop that list for me today is that pop is loved by God. Not some version of my father but him. The man who got angrier as his frustrations grew. That man is loved by God. The man who couldn’t remember that you had been there moments after you left his room. That man is loved by God. The man who yelled and didn’t take his medicine even though he was usually mild-mannered. That man is loved by God. The man who wasn’t a perfect father to any of his sons, who wasn’t a perfect brother or a perfect friend. That man is loved by God.

I tell you that like Lazarus in the gospel and like Mardell Culley who lived his last days in a nursing home completely against his best will—like these men who are loved by God—you and I are also loved. Lazarus and my father, men who reflect a truth that is so large it’s incredible, are mirrors for us today: we, as we are, sit loved by God. We, imperfect as we are, are perfectly acceptable to God. We, with our bruises and our egos and our faults, are wanted and desired so by God that Jesus comes to us and offers a splendid future where resurrection is normal.

Resurrected life, in part, means life where God is immediately present. I cannot imagine all that it means, but living on that other side of breath has to mean living in response to the limitless freedom that comes with no pain and only love. What would that be for you? Would it be a meeting with some family member who has died? Would your resurrected life look like lowered blood pressure or stronger legs so that you could walk or run or leap as long as you want? Would resurrected life mean courage and the absence of fear? Would it mean that you could rest without having so many things to do? These words in John’s gospel pull us to embody what it means for God to be immediate and present. That’s our invitation today.

Among my last words to my father was a prayer. I asked him at the acute care hospital in Searcy whether I could pray with him. He bowed his head, tipping the white rain cap he was wearing. He was fond of those hats—hats in general. He had a large leather hat that was probably as old as me, but in this case, he wore a white hat with a thin blue stripe. When he turned to bow, I took his thin, frail arm and bowed my head. He prayed with me, for what I think was the first time, if I don’t get count thanksgiving for a meal.

When I last spoke with pop, it was days later, Monday, Christmas Eve. Aunt Lynnie called while she at the nursing home and gave daddy the phone. We talked briefly—him asking about Bryce and Dawn, me asking about him and if he’d gotten adjusted to being back at Robinson Nursing Home. Aunt Mose was coming into the room while we were on the phone. There was a lift in my father’s voice. He wasn’t moaning or whispering. He wasn’t muttering the way he often had when he was upset or ready for you to leave his company. I thought he was getting better. I didn’t know he was leaving. I didn’t know at the time that his was the tone of a man getting ready to respond to the immediate presence of God. I’d like to think that my father’s favorite holidays were the ones where he bought some of us gifts. But Daddy would celebrate Christmas thinking of Jesus who he would soon see. My father had his best Christmas ever this year. Even with the lack of an appetite. Even with the chest pains which caused our final alarms. Daddy knew Tuesday and Wednesday that he was going the way his brothers had gone, the way Lazarus had gone. He would see the Lord, the giver of Life. Mardell Culley got the confirmation and the promise.

Pray with me: Oh, God who gives resurrected life, thank you for the chance to know my father, the opportunities to love him and be loved by him. Thank you for every person who showed him kindness, who aided him in recovering and healing. Thank you for his sisters, these beautiful women who have suffered all these times in closing the coffins of their brothers and for how you have sustained them under such grief. Thank you for my brothers and our relatives who have all had our own unique relationships with my father and for how you have blessed us with memories to cherish. Now, Lord, give us unwavering faith, as we leave this place, even if that faith is thin or frail or hardly visible. Grant that we may see the true beauty of this beloved man, and grant that we may discern the true beauty of his savior. Open our eyes to the wonder of every possibility that comes with life in you. Keep company with us from this day on so that we might live as if death will, indeed, come for us. Convince us of your promises to us and confirm your love for us as people who can only accept your unconditional love. We ask these things in the name of the One who beat death and whose victory changed everything, Jesus. Amen.

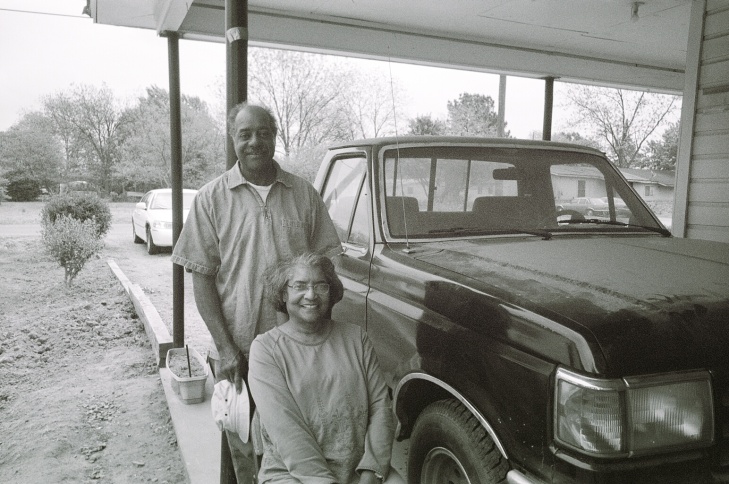

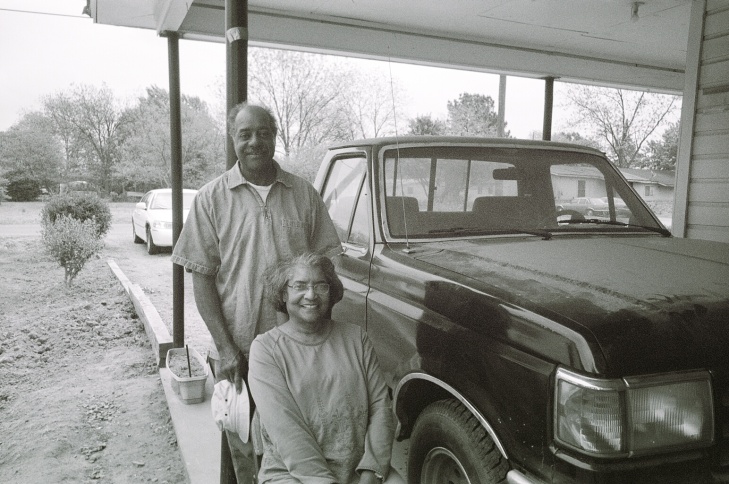

My Dad with his sister, auntie Lynnie a few years ago

Yesterday afternoon, the afternoon of Easter, Dr. Gardner C. Taylor died. I will reflect more on his passing, particularly as I said to Dawn on the poetic nature of him dying on Easter. It was fitting in many ways. But here is a quote from our interview with him in 2011, when his voice was as strong as a few months ago when he and Mrs. Taylor wished us a Happy New Year.

Yesterday afternoon, the afternoon of Easter, Dr. Gardner C. Taylor died. I will reflect more on his passing, particularly as I said to Dawn on the poetic nature of him dying on Easter. It was fitting in many ways. But here is a quote from our interview with him in 2011, when his voice was as strong as a few months ago when he and Mrs. Taylor wished us a Happy New Year.